My Name Shall Be There

1 Kings 8: 27-30

Home Moravian Church, November 17, 2024 (anniversary lovefeast)

November 13, 1771, was a great day in Wachovia: crowds of people, lots of band music, and worship all day long. It was the day of consecration for Salem’s new congregational building, and also the official beginning of the Salem Congregation. During a noon lovefeast, Brother Johann Michael Graff read scripture texts drawn on previous important occasions. Among them was the text drawn on February 14, 1765, when the site for Salem was selected: from First Kings, chapter 8: “Let thine eye be opened toward this place day and night, even toward the place of which thou hast said, ‘My name shall be there.’”[1]

What does it mean to us, that God’s name is here? Biblical answers would include the presence of God’s authority (in Exodus, Moses asks God’s name so he can back his approach to Pharaoh with identifiable power); the reminder that what happens here is attached to the God’s reputation (many Psalms ask God to act “for your name’s sake”); and the way that we name God in our worship by naming God’s character and works (the almighty, the all merciful, the creator). We proclaim these meanings each Sunday with this same text on the front of our bulletin: …the place of which thou hast said, ‘My name shall be there.’”

How fitting that this text was called to mind on the day eighteenth-century Moravians established this congregation and consecrated a worship space. In Salem as in its biblical setting, this text voiced the fulfillment of a dream.

King David’s dream was to build a temple. David, who united all the tribes under his rule, brought to Jerusalem the Ark of the Covenant, Israel’s most sacred object; and he dreamed of building a temple as the Ark’s permanent home.

But God said no. David had to cede that dream to Solomon, his son and successor. And despite Solomon’s achievements and legendary wisdom, his record is, shall we say, complicated. Though the laws of Deuteronomy forbade marriage to non-Israelites, Solomon married an Egyptian pharaoh’s daughter. Though the laws of Deuteronomy were very strict about where worship and sacrifice could be offered, Solomon offered them elsewhere. And although God gave Solomon the job of building the Temple, Solomon built his own palace first. As one commentator writes, “Solomon loved God, but he had other loves as well, and his priorities were not always right.”[2]

When he did build the Temple, though, he used all his kingly power to do it up right, as First Kings is happy to show us: Chapter 6 walks us over every cubit, pointing out every golden accoutrement along the way. And when the project was finished, Solomon dedicated the Temple in the grandest of ceremonies.

With all the people assembled, amid sacrifices of “so many sheep and oxen that they could not be numbered,” the priests brought the ark to the Temple. As the holy space filled with a cloud—the glory of the Lord—Solomon declared to the Lord, “I have built you an exalted house, a place for you to dwell in forever.”

Solomon the king then launched into a speech as kings do, retelling the story of the building project as a sign that God fulfills all God’s promises; and then, he began to pray.

And what a prayer! With grand and powerful words befitting his wisdom, Solomon voiced adoration and acknowledged God’s promise-keeping and favor, introducing as evidence the Temple—the place of God’s presence, represented by God’s name. Solomon prayed:

May your eyes be open toward this temple night and day, this place of which you said, ‘My Name shall be there,’ so that you will hear the prayer your servant prays toward this place. Hear the supplication of your servant and of your people Israel when they pray toward this place. Hear from heaven, your dwelling place, and when you hear, forgive.

In addition to the Bible I’m much devoted to a little book called The Elements of Style by William Strunk and E.B. White, a classic guide for those who wish to write English well. One rule I learned from this book is to put the most important word at the end of the sentence—or, in this case, the end of the prayer. After all Solomon’s eloquence, all his speechifying, all his adherence to formula and all the sweep and drama of his oration, he ends this part of his prayer with the most important word: Forgive.

I didn’t see that coming. Did you?

When you hear, forgive. Not, “When you hear, notice the grandness of our words.” Not, “When you hear, notice the greatness of our project.” Not, “When you hear, think about how you might reward us.” But: When you hear, forgive. This is not the prayer of a person who knows he is powerful. It is the prayer of a person who knows he is vulnerable.

Solomon then walks God through some scenarios of likely sin, and potential catastrophe, and resulting prayers in Israel, with some hope of how God might respond. For example:

When your people Israel have been defeated by an enemy because they have sinned against you, and when they turn back to you and give praise to your name, praying and making supplication to you in this temple,then hear from heaven and forgive the sin of your people Israel….

When the heavens are shut up and there is no rain because your people have sinned against you, and when they pray toward this place and give praise to your name and turn from their sin because you have afflicted them,then hear from heaven and forgive the sin of your servants, your people Israel….

When famine or plague comes to the land, or blight or mildew, locusts or grasshoppers, or when an enemy besieges them in any of their cities, whatever disaster or disease may come,and when a prayer or plea is made by anyone among your people Israel—being aware of the afflictions of their own hearts, and spreading out their hands toward this temple—then hear from heaven, your dwelling place. Forgive and act; deal with everyone according to all they do, since you know their hearts (for you alone know every human heart).

God knows every human heart, as well as every human name. God knows our names much better than we know God’s. “God” is a word we use; it has been traced all the way back to an ancient form of German and might mean something like, “That which is invoked.” So “God” is what we call the being we call upon. In the book of Exodus, when Moses asks God’s name, God replies with something scribed as Yahweh, usually translated with something like “I am who I am.” God is who God is; and God is the one we call upon. Concerning God’s name, that is all we know, and all we need to know; but God knows each of our names. So a better question than, “What does it mean to us that God’s name is here?” might be, “What does it mean to God that our names are here?”

When our names are here, it means that we make ourselves vulnerable. It means that we open ourselves in confession, to the risk of God’s judgment. We openly admit our need of forgiveness. To have our names in this place, committed to this congregation, is to acknowledge our sorry imperfection and to have confidence that we are loved anyway. That we are forgiven anyway. To put our names here is to acknowledge we need forgiveness every single day.

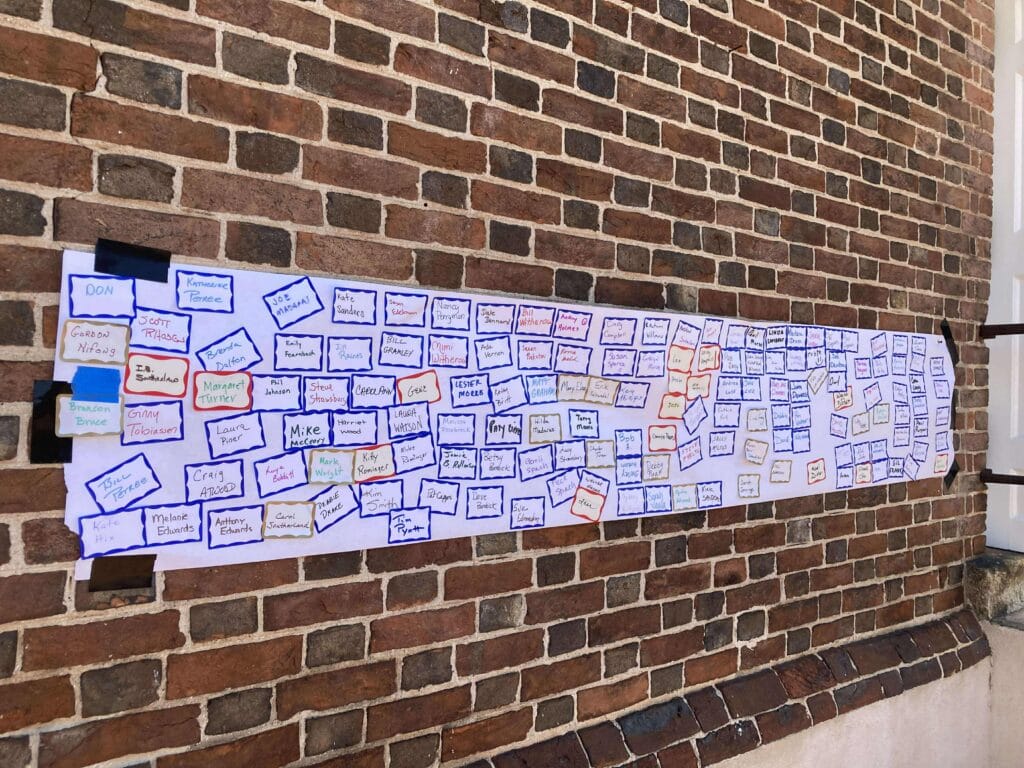

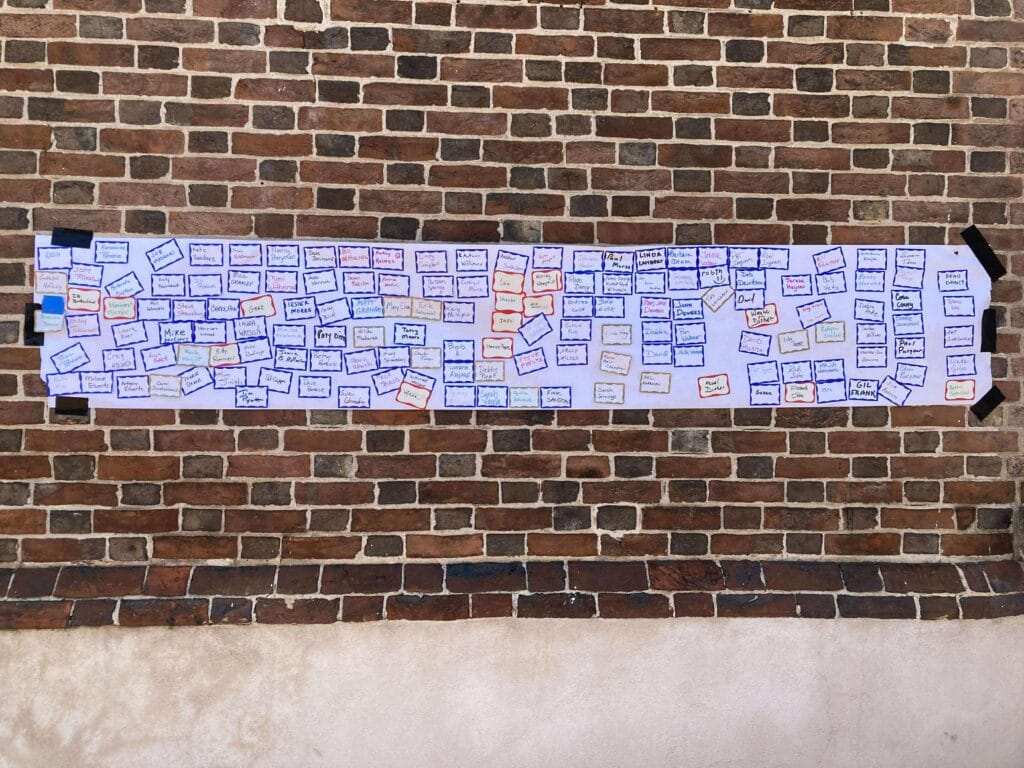

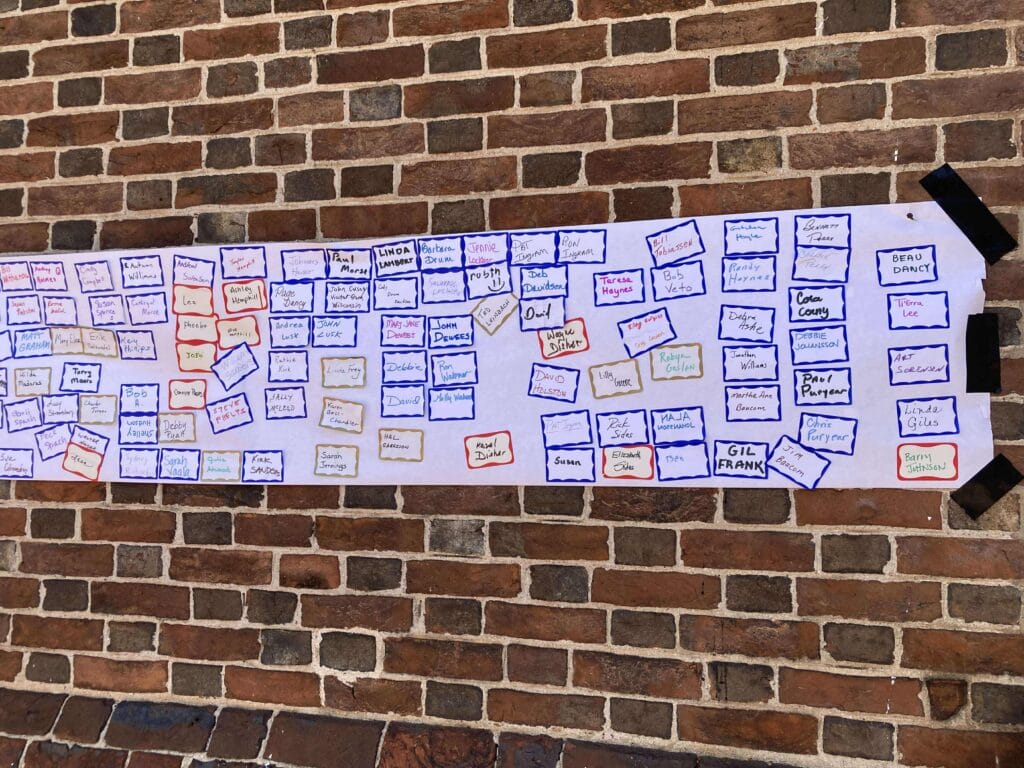

When you came in today, you were encouraged to write your name on a sticker and put that sticker on your person. Maybe you did, maybe you didn’t. Maybe you thought, “Oh, everyone here knows me,” or, maybe you thought, “Oh, I don’t want everyone here to know me.” Maybe you just came in late and didn’t get a sticker. But think about what it means that your name can be here!

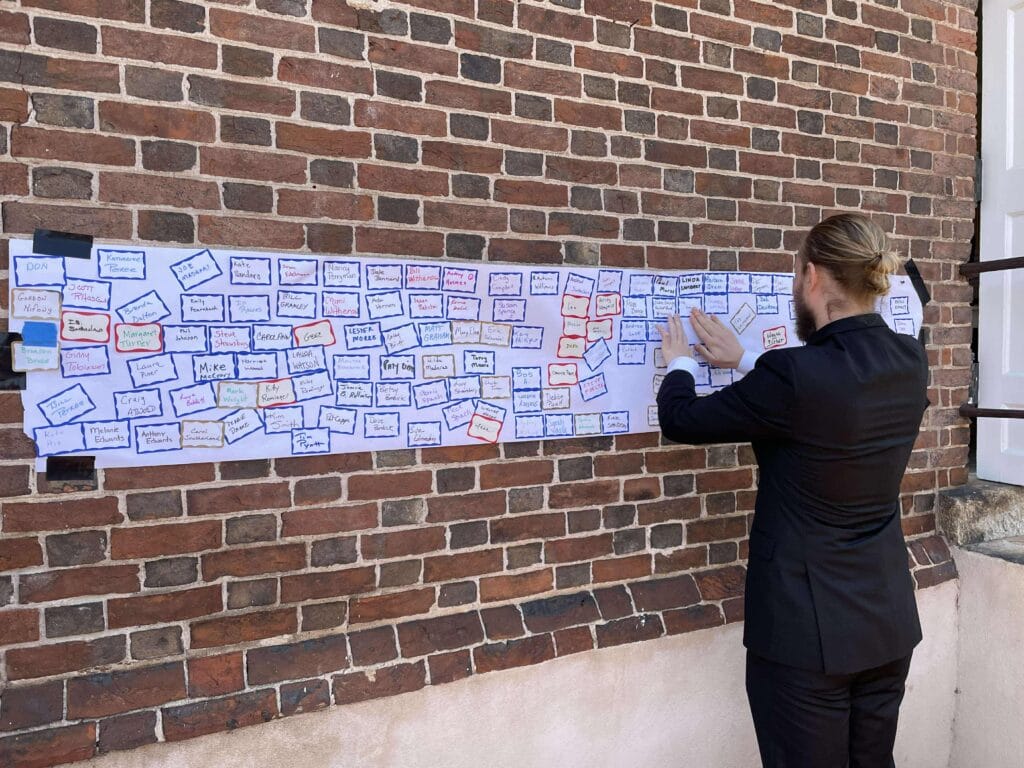

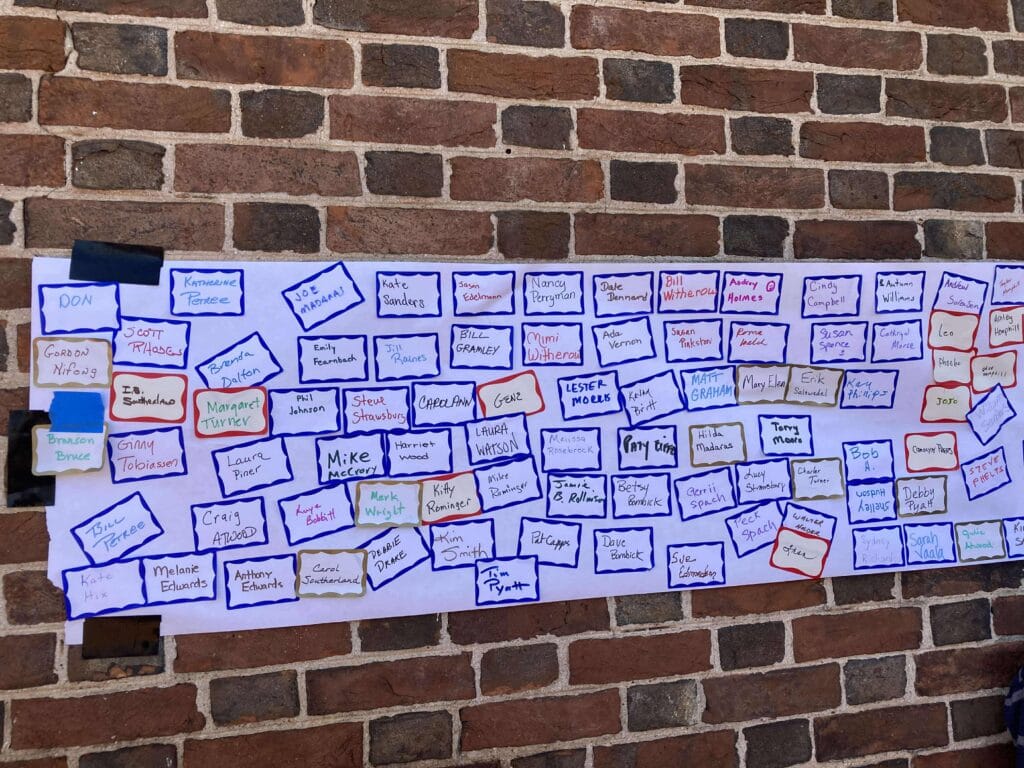

When you leave today, you’ll find on the outer walls of our sanctuary some big white pieces of paper. I encourage you to peel off your sticker and affix it to one of those papers. If you didn’t make a sticker, don’t worry, there are stickers in the pews. You don’t have to be a member; your name is here today. A little while ago we sang a hymn that said, “God is here!” This is our chance to say: “So am I. Because I need to be.”

Among the changes in recent years at Baptist Hospital is that you can no longer just walk in. Now you have to show your ID and get a sticker with your name and a bar code on it, which you have to wear as you pass through the buildings.

This irritation actually began during the pandemic shutdown. I guess it was a way of assuring that anyone in the building had a reason to be there. And the first time I left the hospital with one of those stickers on my shirt, I saw that in the empty, echoing parking deck, people had peeled off their stickers and slapped them on the concrete beams overhead. So I did, too. And I did it every time after that. In that strange era of separation and loss, those bar-code stickers, which began to cover those concrete beams, seemed to me an insistent claim of presence, saying, We were here. In an hour of need and struggle, we were here. God help us, our names are here.

The hospital administration eventually pressure-washed all those stickers off the beams, and now you give your sticker to the parking attendant to get out of the deck for free. But I remember the stickers on the beams. It meant a lot to put mine there. In that hard time, my name was there. And God helped me, because I needed it.

Here in this place that is under God’s authority; here in this place where God acts for God’s name’s sake; here in this place where we name God by naming God’s character and works, the better to know this God who knows us so well: our names are here not because we are noble, or gifted, or wealthy, or powerful, or proud of being descended from multiple generations who built and sustained this church. Some of us may be any or all of these things; but when we put our names here we surrender these things. We put our names here not to be noticed for the grandness of our words or the greatness of our project; not so that God and humanity might ponder how to reward us; but because we need God, who knows us each by name, to help us, and especially to forgive us for the messy way we manage our lives.

To put our names here is to confess our need, and to be okay with needing. It is safe to have a need here. It is safe to confess our need for God and for one another. It is safe to confess our imperfections and our need for forgiveness. With God’s eyes open toward us, and our hearts open toward God, let us say: Our names shall be here, where it is safe to be known, and blest to be forgiven. Amen.

[1] Adelaide L. Fries, trans. and ed., Records of the Moravians in North Carolina (Raleigh: North Carolina Historical Commission, 1922), I.445.

[2] Choon-Leong Seow, “The First and Second Books of Kings,” New Interpreter’s Bible (Nashville: Abingdon, 1995), III.4.